A court in Uganda has sentenced a man found guilty of trafficking wildlife products to life in prison. However, the sentence has left wildlife officials and human rights activists divided over whether it fits the crime.

On Thursday, October 20, the Uganda Court of Standards, Utilities and Wildlife sentenced Pascal Ochiba to life imprisonment for illegal possession of wildlife products, including two pieces of elephant ivory weighing a total of 9.55 kg.

It is the country’s highest penalty ever imposed for wildlife violations.

Ochiba was arrested in 2017 for possession of four pieces of ivory and okapi skin. In that case, he was sentenced to eighteen months in prison for both crimes, which he served simultaneously.

Bashir Hangi, a spokesman for the Uganda Wildlife Authority, called Ochiba’s conviction fair: “It was reasonable. It was deserved. But because it was his business, he couldn’t stop the business. So we reviewed the law to achieve that,” spokesman said.

“The Judgment is a bit blunt. And we hope that the judiciary continues to punish other offenders with the same severity,” he added.

Also, read; Chemical Hair Straighteners Linked to Higher Risk of Cervical Cancer in Black Women, Research Shows

Livingstone Sewanyana, executive director of the Foundation for Human Rights Initiative, disagrees. “Life imprisonment should be a sentence served by those who would normally be sentenced to death,” Sewanyana said while demanding that the court reconsider.

The difference in perspectives as regards the sentencing stems from the Uganda Wildlife Act 2019.

Under the new legislation, offenders could face a $5,200 fine, life in prison, or both. It does not offer flexibility in punishment when the product in question is of an endangered species, such as elephants.

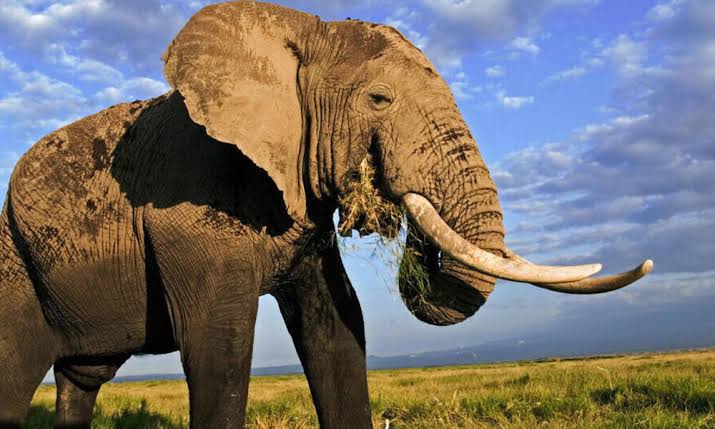

Africa’s elephant populations have been greatly reduced in recent decades by poachers who have killed the animals for their tusks, which remain in high demand in Asia despite international restrictions on the ivory trade.

Uganda is historically known as a trade center for wildlife and its products in East Africa, according to the Wildlife Conservation Society, due to the country’s porous borders, light penalties, and limited ability to combat wildlife crime.