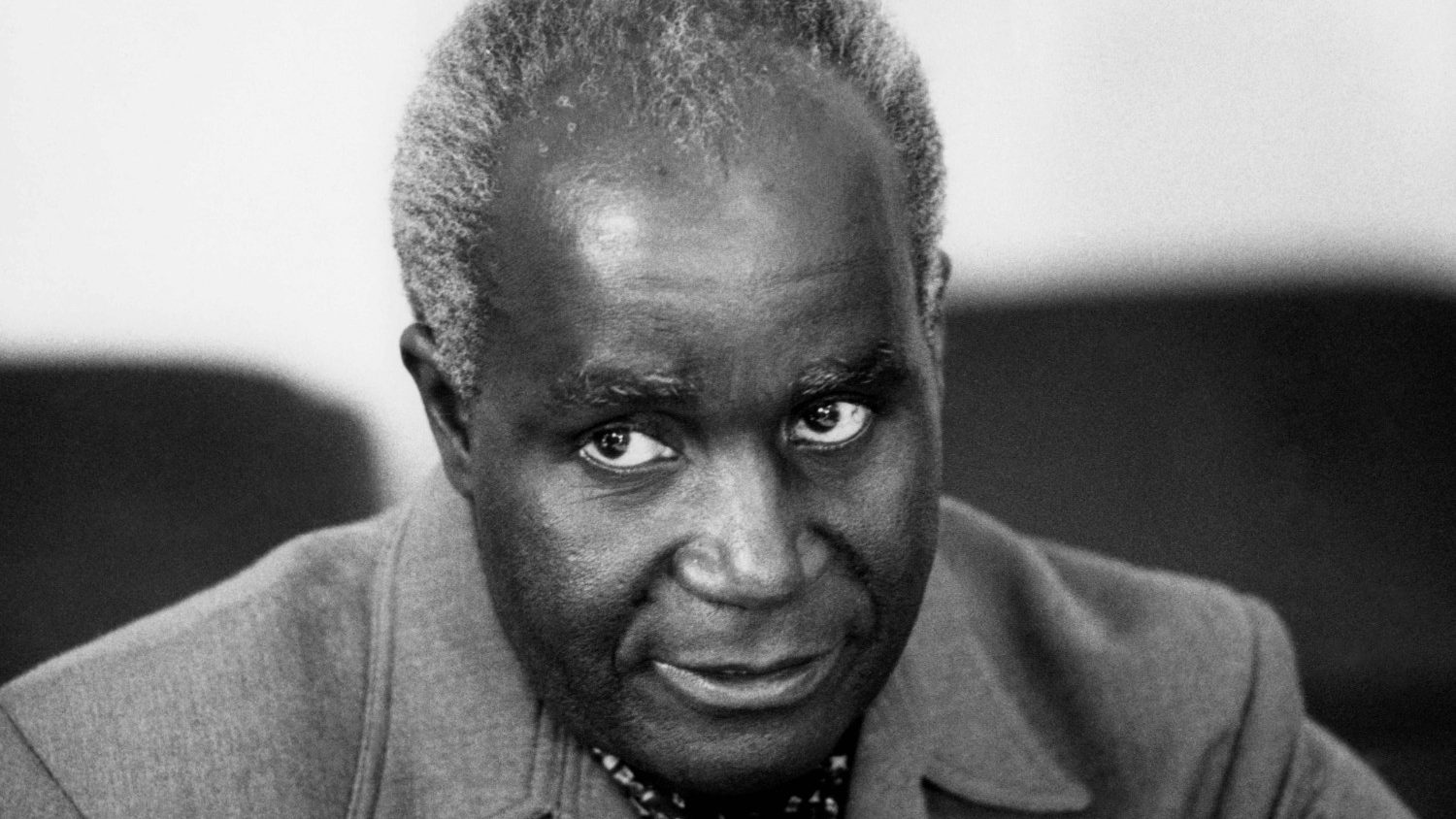

Kenneth David Kaunda, born on April 28, 1924, was the first president of Zambia from 1964 to 1991. He played a crucial role in Zambia’s fight for independence from Rhodesia and white minority rule.

Kaunda faced imprisonment and conflicts with rival groups due to his dedication to the independence movement.

During his presidency, David Kaunda held emergency powers and eventually banned all political parties except his own United National Independence Party.

He governed in an autocratic manner, facing economic challenges and opposition to his leadership. He took a stance against the Western world and implemented socialist economic policies, though they did not yield significant success.

Eventually, due to international pressure for more democracy in Africa and ongoing economic struggles, Kaunda was forced out of office in 1991.

Nevertheless, he is widely recognized as one of the founding fathers of modern Africa.

The early life of David Kaunda

David Kaunda, the youngest of eight children, was born in Chinsali, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) in 1924.

His father, Reverend David Kaunda, was a missionary from Malawi, and his mother was a teacher. Growing up, Kaunda received his education at Lubwa Mission. Following in his parent’s footsteps, he became a teacher himself.

After working in various locations, including Tanganyika Territory (now Tanzania) and Southern Rhodesia, Kaunda attended the Munali Training Centre in Lusaka from 1941 to 1943.

He then took up teaching positions at Lubwa Mission and later in Mufulira, where he worked for the United Missions to the Copperbelt (UMCB).

During this time, he also engaged in activities such as leading a Pathfinder Scout group and serving as a choirmaster at a local church.

Throughout his early career, Kaunda was influenced by the writings of Mahatma Gandhi, which deeply resonated with him.

He faced personal hardships, including the loss of his father during his childhood. Despite these challenges, Kaunda’s passion for education and his commitment to serving his community continued to shape his path.

The fight for independence

In 1949, Kaunda worked as an interpreter and adviser on African affairs to Sir Stewart Gore-Browne, a member of the Northern Rhodesian Legislative Council.

This experience provided him with insights into the colonial government and honed his political skills.

Later that year, Kaunda joined the African National Congress (ANC), the leading anti-colonial organization in Northern Rhodesia.

During the early 1950s, Kaunda served as the ANC’s secretary-general and played a key role in organizing its activities.

When the ANC’s leadership disagreed on strategy in 1958-1959, Kaunda led a significant portion of the organization into a new group called the Zambia African National Congress.

In 1951, Kaunda briefly returned to teaching before becoming an organizing secretary for the ANC in Northern Province.

In 1953, he moved to Lusaka and became the Secretary General of the ANC. Kaunda and Harry Nkumbula, the ANC’s president at the time, struggled to mobilize African people against the white-dominated Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

In 1955, Kaunda and Nkumbula were imprisoned for distributing subversive literature, an experience that further radicalized Kaunda.

As Nkumbula became more influenced by white liberals and inclined to compromise on majority rule, Kaunda grew apart from him.

Kaunda broke away from the ANC and formed the Zambian African National Congress (ZANC) in 1958. ZANC was eventually banned, and Kaunda was imprisoned for nine months.

Upon his release, Kaunda became the president of the United National Independence Party (UNIP) in 1960.

He led a civil disobedience campaign and ran as a UNIP candidate in the 1962 elections. UNIP formed a coalition government with the ANC, and Kaunda was appointed as Minister of Local Government and Social Welfare.

In 1964, UNIP won the general election, and Kaunda became the first prime minister of independent Zambia. Later that year, he became the country’s first president, with Simon Kapwepwe as the vice president.

David Kaunda as President

During his presidency, David Kaunda ruled Zambia under a state of emergency and became increasingly intolerant of opposition.

He banned all political parties except his own UNIP (United National Independence Party) following violence during the 1968 elections.

David Kaunda faced challenges from the independent Lumpa Church led by Alice Lenshina, which rejected earthly authority and clashed with UNIP.

This led to a state of emergency being declared, resulting in the deaths of villagers and the flight of Lenshina’s followers. The Lumpa Church was banned, and the state of emergency remained in place until 1991.

David Kaunda established a one-party state in 1972, eliminating opposition and keeping his enemies at bay.

He fostered a personality cult and developed an ideology called “Zambian Humanism.” He signed treaties with China and the Soviet Union, and Zambia hosted various Marxist revolutionary movements, serving as a launching pad for attacks against neighboring countries.

In terms of education, Kaunda aimed to improve access and quality. He provided free exercise books and pens to all children, although not every child could attend secondary school.

The University of Zambia was established in 1966, and other vocational institutions were also set up. Economically, Zambia faced challenges, with a slump in copper prices and a balance of payments crisis in the 1970s.

Kaunda implemented national development plans and pursued a policy of acquiring equity in key foreign-owned firms, leading to the formation of state-owned corporations.

However, economic difficulties persisted, and Zambia became heavily indebted. Kaunda implemented measures recommended by the IMF, including ending price controls and subsidies, which caused social unrest.

In foreign policy, Kaunda supported the anti-apartheid movement, opposed white minority rule in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), and provided support to African liberation movements.

He was an advocate of the Non-Aligned Movement and had friendly relations with China, Yugoslavia, and Iraq.

Overall, Kaunda’s presidency was marked by political repression, economic challenges, and active involvement in regional and international affairs.

David Kaunda’s Fall from Power

In 1990, the situation in Zambia reached a critical point. There were three days of rioting in the capital, prompting President Kaunda to announce a referendum in October to decide whether other political parties should be allowed.

However, he argued in favor of maintaining his party’s monopoly, fearing that a multiparty system would lead to chaos.

Shortly after the announcement, a dissatisfied officer went on the radio and declared that Kaunda had been overthrown.

Although the coup attempt was controlled within a few hours, it was evident that Kaunda and his party were in a vulnerable position.

To appease the opposition, Kaunda rescheduled the referendum for August 1991, as critics argued that the original date did not allow enough time for voter registration.

While Kaunda expressed a willingness to let the Zambian people decide on a multiparty system, he maintained that only a one-party state could prevent tribalism and violence from tearing the country apart.

However, mounting pressure from the opposition forced Kaunda to change his stance by September. He canceled the referendum and instead proposed constitutional amendments to dismantle his party’s monopoly on power.

Additionally, he announced a snap general election for the following year, two years earlier than scheduled. In December, Kaunda signed the necessary amendments into law.

During the elections, the Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD), led by trade union leader Frederick Chiluba, achieved a landslide victory, ousting UNIP from power.

In the presidential election, Kaunda suffered a resounding defeat, receiving only 24 percent of the vote compared to Chiluba’s 75 percent.

UNIP’s representation in the National Assembly was reduced to just 25 seats. One contentious issue during the campaign was Kaunda’s plan to allocate one-quarter of the nation’s land to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, an Indian guru who promised to create utopian agricultural communities.

Kaunda was forced to deny practicing Transcendental Meditation in a televised interview.

On November 2, 1991, Kaunda peacefully handed over power to Chiluba, becoming the second mainland African head of state to allow free multiparty elections and peacefully relinquish power after losing. The first leader to do so was Mathieu Kérékou of Benin in March of the same year.

Retirement

After Frederick Chiluba became the president, he tried to deport Kaunda by claiming that David Kaunda was not a Zambian but actually from Malawi, a neighboring country.

Chiluba’s government, dominated by his party MMD, amended the constitution to prevent individuals with foreign parentage, like Kaunda, from running for the presidency.

This was done to ensure that Kaunda couldn’t participate in the next elections in 1996. Eventually, Kaunda retired from politics after being accused of involvement in a failed coup attempt in 1997.

Also read: 8 Reasons Why You Should Travel To Zambia

Following his retirement, Kaunda dedicated himself to charitable work and became involved with various organizations. From 2002 to 2004, he held the position of African President in Residence at Boston University.

Conclusion

Kenneth Kaunda, the first President of Zambia and a prominent figure in the country’s struggle for independence, had a complex legacy.

While some criticized his methods and alliances with the Soviet Union and Cuba, labeling him as a misguided socialist revolutionary and autocratic ruler due to his “one party” state, many Africans hold him in high regard.

This is primarily because of his unwavering opposition to apartheid, which earned him recognition as one of the key founding leaders of modern Africa.

Source

https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Kenneth_Kaunda