When Africans or members of the global African diaspora assert that ancient Egyptians were Black, a common rebuttal arises: “Why are you so obsessed with skin color?” On its surface, this sounds like a neutral plea for colorblindness. But beneath that surface lies a familiar pattern — gaslighting. That is, psychological manipulation where the oppressor accuses the victim of the very behaviors the oppressor exhibits.

Skin color in the last millennium has not been neutral in the global imagination. It was used to justify slavery, colonialism, apartheid, and pseudoscientific racial hierarchies. Thus, when Africans reclaim ancient narratives — especially about Egypt — they are not being “obsessed” with skin color. They are deconstructing centuries of theft, denial, and distortion.

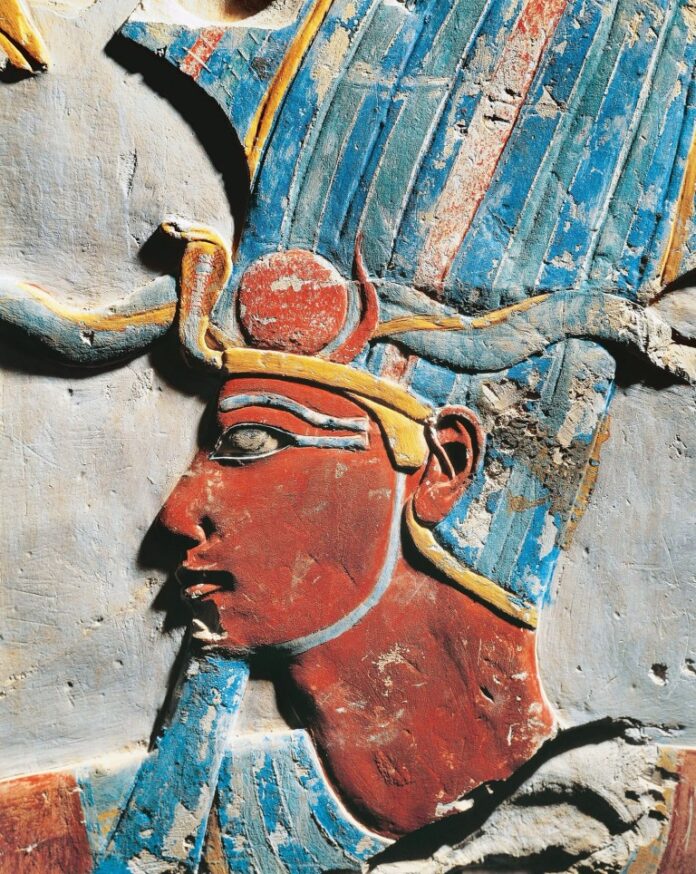

In contrast, in ancient Egyptian symbolism, black skin tone represented fertility, rebirth, and the rich, life-giving soil of the Nile. The god Osiris, ruler of the afterlife, was often depicted with black skin—such as on the 11th Dynasty coffin of Ikhernofret (c. 2000 BCE)—to symbolize resurrection. Statues like the black granite seated figure of Pharaoh Mentuhotep II (c. 2050 BCE) further reinforced this symbolism, combining royal power with regenerative themes. Black skin in Egyptian art carried deeply spiritual, protective, and agricultural meaning.

European artists painted Jesus what?

Chinese artists painted Buddha what?

The ancient Egyptians painted Osiris what?

Let’s be clear: the question is not whether Africans are obsessed with skin color — it is why certain people are so threatened when Egypt is called what it was — an African, Black civilization.

⸻

2. Cross-Cultural Comparisons: Skin, Power, and Cultural Legacy

Skin color has carried symbolic and political weight across many civilizations — not just African. In India, light skin was associated with higher caste status. In ancient China, light skin signified elite indoor labor, while tanned skin implied field work. In European history, paleness was a sign of nobility, while suntanned laborers were peasants. This isn’t just Africa’s story — it’s a human story.

So when African people recognize Blackness in their ancient past — and especially in Egypt — they’re doing what every other culture has done: linking ancestry to legacy. The issue arises not because they do this — but because they do so successfully, in a world that has long denied them greatness.

Contrast this with how Greeks are allowed to revel in Sparta or Italians in Rome without accusation. No one asks an Italian, Frenchman, or Briton if they’re “obsessed with gladiators” when they celebrate Roman aqueducts. No one tells the British they’re obsessed with monarchy when they proudly name their kings. Yet when Africans assert that ancient Egyptians were Black — and that this matters — the accusation is: obsession.

That’s not critique. That’s discomfort with African self-esteem.

3. Vivid Examples and Evidence: Black Egypt Was Never a Secret

Let’s take a short journey through time — in paintings, language, science, and philosophy — to show that the identity of ancient Egyptians was never mysterious until racism made it so.

Visual Art:

The Egyptians depicted themselves with dark reddish-brown to deep brown skin — distinct from the pale-skinned Libyans and lighter-toned Asiatics. In the tomb of Ramses III, the four races known to Egyptians are portrayed: Egyptians, Nubians, Libyans, and Asiatics. Egyptians and Nubians share similar skin tones; Libyans and Asiatics are painted lighter. The Egyptians knew they were African — and they showed it.

Language:

Ancient Egyptian is part of the Afroasiatic language family. The root proto-language likely emerged in northeast Africa — perhaps around modern-day Sudan or Chad. This family includes other African languages like Somali, Oromo, and Hausa. You don’t inherit a language family from a people unless you’re closely tied to them culturally and demographically.

DNA and Skeletal Analysis:

Multiple studies — including those by Keita, Kemp, and Zakrzewski — show that predynastic and early dynastic Egyptians had craniofacial features most similar to East African populations. As for genetics, early Nile Valley populations carry lineages such as E1b1a, E-M78, L2a1 and L3 — all rooted in Africa.

Philosophical Witnesses:

Herodotus, the Greek historian, referred to the Egyptians as having “dark skin and woolly hair.” Aristotle said Egypt was the oldest political model. Diodorus Siculus confirmed that Ethiopians (Nubians) were believed to have colonized Egypt. These classical sources saw Egypt as African — before Europeans began “whitening” the narrative.

So again, when Africans assert their connection to ancient Egypt, they are not obsessed with color. They are obsessed with truth.

⸻

4. Critical Analysis of Misconceptions: The Real Obsession

Let’s flip the question. Who is really obsessed with skin color?

Is it the African child who finds pride in knowing their ancestors built pyramids — or the textbook writer who erased those faces from history?

Is it the scholar reclaiming African science — or the colonial system that banned African languages, de-Africanized Egyptian statues, and classified Nubians as “lesser cousins”?

Consider this: from the 19th century onward, Western scientists mutilated mummies to measure skulls, lips, and noses. They bleached frescoes, destroyed noses on statues, and fabricated racial categories to exclude Africa from history. This wasn’t science — it was obsession.

And when Africans merely point out the evidence? The same people call them “race-obsessed.”

Let’s be blunt: accusing Africans of obsession when they reclaim stolen legacies is like stealing someone’s home, then calling them greedy or petty when they ask for the deed back.

5. Narrative Style and Engagement: History as Theft, Reclamation, and Resistance

Imagine a museum. Inside are gold, statues, and scrolls taken from Egypt — but the plaques call the people “Mediterranean,” the language “Middle Eastern,” and the skin tones “ambiguous.” A Black child walks through, sees images of people with hair like his, noses like his, but signs that refuse to admit the connection.

He says, “These were my ancestors.”

A voice replies, “You’re obsessed with race.”

That is gaslighting — in its purest form.

It’s the same tactic used in colonial classrooms where African children were taught that civilization began in Greece, that Egypt was a “mystery,” and that Blackness meant savagery. So when we challenge that? When we say Egypt was Black? We’re not obsessed — we’re correcting the record.

And sometimes, correction looks like confrontation.

Yes, skin color matters — because colonialism made it matter. Because race was used to enslave, categorize, and exclude. Because centuries of pseudo-history stripped Blackness from African greatness. Because even in 2025, people like “Jeremy” say “Egyptians were never negro.”

In that context, asserting the Black identity of ancient Egyptians isn’t obsession. It’s resistance. It’s memory. It’s dignity.

⸻

To say that Africans are obsessed with skin color because they affirm ancient Egypt’s Black identity is not only dishonest — it’s gaslighting. It deflects from the centuries-long campaign to whiten African history, steal African genius, and marginalize Black contributions to global civilization.

Skin color is not the point. The point is truth, power, and the right to self-define. When Africans look to the pyramids and say, “That is ours,” they are not asking for permission. They are reclaiming what was never lost — only hidden.