South African protest songs have long been misunderstood outside the country’s borders, and once again, one of them is at the centre of an international firestorm. The song Dubul’ ibhunu — commonly translated as “Kill the Boer” — has ignited global outrage after tech billionaire Elon Musk shared a video of it being sung at a political rally. But to understand the song, one must first understand its history — and South Africa’s painful path through apartheid.

Over the weekend, Musk tweeted that a “major political party” in South Africa was “actively promoting white genocide,” referring to the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and its leader, Julius Malema, who was seen singing the song at a rally on Friday.

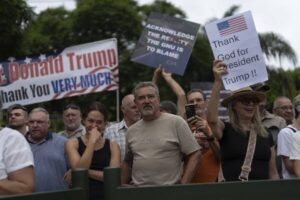

The tweet quickly escalated, pulling in high-level political figures from the United States. US President Donald Trump — now in his second term and known to be a close ally of Musk — shared the post on Truth Social with a warning about “violence against white people.” Secretary of State Marco Rubio joined in, calling the song “a chant that incites violence” and urging South Africa to protect its “disfavored minorities,” while offering Afrikaners the option of resettling in the US.

But is Dubul’ ibhunu truly a call for violence? Or has its historical and cultural meaning been misrepresented?

A Song Rooted in Resistance

Dubul’ ibhunu, which in isiXhosa translates to “Shoot the Boer,” dates back to the height of the anti-apartheid struggle in the 1980s. At the time, black South Africans were fighting for their lives and dignity under a brutally enforced regime of racial segregation. In that context, the “Boer” — often referring to Afrikaans-speaking white farmers — was not just an individual, but a symbol of the oppressive apartheid state.

Much like other resistance songs around the world, its language is militant, emotional, and urgent. It was never meant to be a literal call to kill, but rather a rallying cry to overthrow an unjust system. “Boer” in this context stood for the institutions and forces of racial domination, not all white people.

South Africa’s Equality Court has ruled on this multiple times, most recently in 2023, finding that the song, when sung in political or cultural contexts, does not constitute hate speech. The court acknowledged the song’s history as part of the anti-apartheid movement and stressed that it must be understood within that frame.

Why the Song Still Resonates

Today, “Kill the Boer” continues to stir emotions — especially among young, black South Africans who still live with the socioeconomic consequences of apartheid. For many, the song is not about race-based violence, but about unfinished justice. Land ownership remains starkly unequal. Poverty is still racialized. And while political apartheid may have ended in 1994, economic apartheid lingers.

EFF leader Julius Malema defends the song as an integral part of South African heritage. “We have not called for the killing of any white person,” he has stated in the past. “We are singing about the system. We are singing about our history.”

Also, read: South Africa Partners with World Bank in $3 Billion Plan To Reshape It’s Biggest Cities

Why the Trump Administration Cares

So why has the Trump administration taken such a keen interest in this? The president has long aligned himself with a global movement concerned about what it sees as “anti-white” sentiment — often rooted more in perception than fact. Trump has previously claimed that white farmers in South Africa are being persecuted and killed en masse, a claim that human rights organizations and South Africa’s own data have refuted.

By weighing in again — this time with the backing of Musk and Rubio — the administration may be hoping to score political points with right-wing voters at home, particularly those sympathetic to white nationalist talking points. The framing of “Kill the Boer” as a literal call for genocide fits neatly into that narrative.

What Gets Lost in Translation

The real tragedy of this debate is how easily South Africa’s complex history gets flattened into a soundbite. Dubul’ ibhunuis not a modern incitement to violence — it is a memory, a protest, and in some ways, a cry for help. It reminds black South Africans of what their parents and grandparents endured. It speaks to a wound that hasn’t fully healed.

To view it as a genocidal chant is to miss everything about what made it necessary in the first place.

Conclusion

Words matter. But so does context. “Kill the Boer” is not a campaign to eliminate a race — it’s a reminder of the fight against a system that tried to eliminate a people’s dignity. In a world quick to outrage but slow to understand, it’s more important than ever to look deeper.

South Africa’s journey to justice is ongoing. And like all nations shaped by trauma, its songs carry pain, defiance, and memory. To silence those songs without listening to their meaning is to deny the struggle they came from.