Congolese prime minister and independence leader Patrice Lumumba was slain by firing squad on January 17, 1961, exactly fifty-nine years ago today.

In the months running up to his murder, the world focused on the Congo as a critical battlefield for Cold War politics. European and American media coverage of the “Congo Crisis” demonstrated a fascination with Lumumba and an attempt to portray him as an autocratic ruler.

Media outlets, for example, used the headline “Lumumba as a Congo ‘King.'” The New York Times chose the title of “‘Messiah’ in the Congo.'”

Among the nonstop international media coverage of Lumumba’s life, leadership, and death, one strange headline sticks out for focusing on an intriguing man next to the Congolese leader.

Three months before the killing that would rock the world and weaken Africa’s liberation drive, the Baltimore Afro-American published an article titled “The Woman Behind Lumumba.” The article itself was quite short:

Behind every famous man there is a woman.

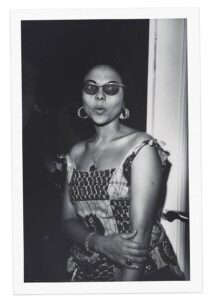

According to the London Daily Mirror, Madame Andree Blouin is the power behind the actions to Congo leader Patrice Lumumba.

She is 42, half-African, half French and married to a French mining-engineer.

Officially, she holds the position of Chief of Protocol, but Justin Bomboko, the Congo’s Foreign Minister, told the Congo Senate that she is trying to run the country and was a Communist.

Who was Andrée Blouin? Was she really the woman behind Lumumba? The article’s four sentences do not tell us much about her. They do, however, speak volumes about the reasons for which politicians and the media viewed her as a suspicious and illegitimate presence in Lumumba’s government. And, even more importantly for us today, they offer lessons about the historically racialized and sexualized representations of women of color in politics.

Blouin was born in the Central African Republic in 1921 and spent her early years at an orphanage for “mixed race” children in Brazzaville, French Congo.

She then became an anticolonial activist in what was then called the Belgian Congo. Her frequent migrations between French and Belgian lands provided her with personal experience of each imperial power’s specific cruelties.

While the Belgian practice of sequestering children born to Belgian dads and Congolese mothers in orphanages has recently attracted notice, Blouin’s memoirs.