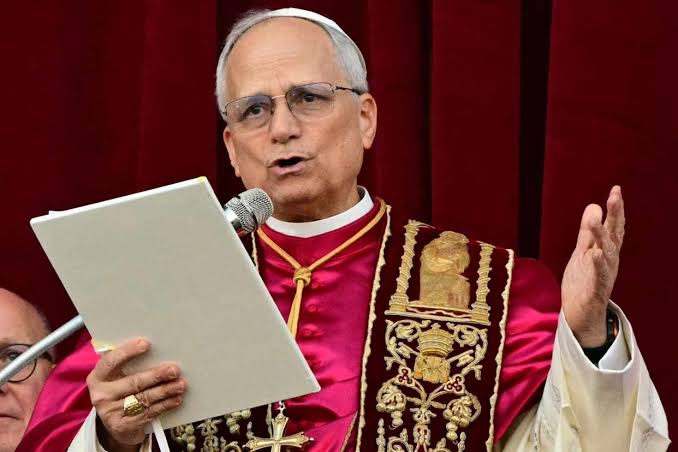

As the world watched Pope Leo XIV step onto the balcony of St. Peter’s Basilica on Thursday, one unexpected detail about the new pontiff began to captivate Catholics across the globe — his ancestral roots may include Black Creole heritage from New Orleans and possibly the Caribbean.

The revelation has been embraced by many, particularly in Africa and Latin America, where Catholic communities say the pope’s lineage offers a deeper, more personal connection to the Church’s new leader. But not everyone in his family sees it that way.

John Prevost, the pope’s older brother who lives in the suburbs of Chicago, confirmed that their maternal grandparents came from Haiti, yet insists the family never identified as Black.

“We just never saw ourselves that way,” he told CNN. “That’s not how we were raised.”

Still, genealogical records and historical research suggest a more complex story.

A Legacy Rooted in the 7th Ward

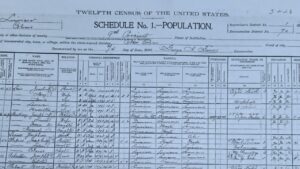

Pope Leo’s maternal grandparents, Joseph and Louise Martinez, were part of New Orleans’ historic 7th Ward — a melting pot of African, Caribbean, and European cultures. According to census records from 1900, both were listed as Black. Joseph, a cigar maker, was recorded as being born in “Hayti,” the 19th-century spelling for Haiti.

The couple were identified as free people of color — a group that had long existed in New Orleans prior to the Civil War. After migrating to Chicago in the early 1900s, they seemingly assimilated into white society.

Jari C. Honora, a family historian with the Historic New Orleans Collection, has spent years tracing the family’s background. He emphasized that the decision to “pass” into white society wasn’t unusual for that era.

“It’s not about calling anyone out,” Honora said. “It’s about honoring the choices people made in a deeply divided society and understanding the nuances of identity, migration, and faith.”

Also, read: Ayra Starr, Tems, Burna Boy, Tyla and Black Sherif Earn 2025 BET Award Nominations

Reactions From Around the World

For Rev. Lawrence Ndlovu, a priest in Johannesburg, South Africa, the discovery of Pope Leo’s heritage came as both a surprise and a point of connection.

“When I saw him, I immediately thought, ‘You don’t look like the typical white pope,’” Ndlovu said. “And when I learned about his roots, I thought — he’s one of us.”

Many in Brazil, a country with a complex racial history and a majority population of Black or mixed-race citizens, have also found encouragement in the pope’s background.

“He knows what suffering looks like,” said Robson Querino do Nascimento, a church maintenance worker in Rio de Janeiro. “If there are people of color in his family, he will understand the poor and the marginalized in a way few others can.”

A Mixed Reaction to Identity

While many are celebrating the new pope’s heritage, others are noting the family’s reluctance to embrace a Black identity as a reflection of generational pressures and cultural context.

“The fact that they passed into whiteness in Chicago doesn’t erase their past,” Honora said. “But it does highlight how fluid and sometimes fragile, racial identity can be in America.”

Edwin Espinal Hernández, a genealogist at the Pontificia Universidad Católica Madre y Maestra in the Dominican Republic, added that his team has uncovered signs that the pope’s grandfather may have been born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

If confirmed, it would further cement Pope Leo XIV’s Caribbean heritage and reinforce what many Catholics around the world are already feeling: that this pope, for the first time in history, may truly represent the diversity of the global Church.

Whether Pope Leo himself will publicly acknowledge these roots remains to be seen. But for now, his story — layered, complex, and unmistakably human — is resonating far beyond Vatican walls.