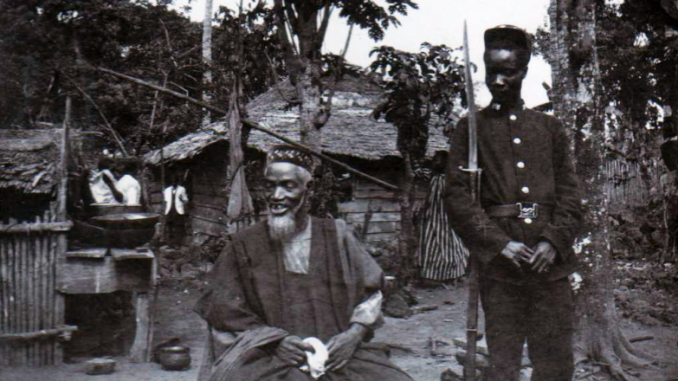

Bai Bureh was a Sierra Leonean ruler, military strategist, and Muslim cleric who led the Temme protest in Northern Sierra Leone in 1898 against British control.

Bai Bureh was born in 1840 in Kasseh, a community near Port Loko in Northern Sierra Leone. Bureh’s father was a Muslim preacher and a powerful Loko warlord who cherished African traditions and values.

His father was a powerful Loko war leader, and his mother was most likely a Temne woman from the area near present Makeni.

As a young man, he was transferred to Gbendembu, a warrior training school, where he gained the nickname “Kebalai,” which means “one whose basket is never full” or “one who is never tired of war.”

In the 1860s and 1870s, Kebalai rose to prominence as a war leader, acting under a Soso ruler in a protracted Jihad to promote orthodox Islamic traditions.

Also read: Queen Idia, the First Queen Mother of Benin Kingdom in Nigeria

Kebalai was a respected monarch of Kasseh, a small kingdom near Port Loko, in 1886, and was given the regal title of Bai Bureh.

The new king quickly earned a reputation for dogged independence, which irritated the British authority in Freetown.

On one occasion, Bai Bureh refused to recognize a peace deal arranged by the British with the Limba without his participation, and on another, he led soldiers on a raid into French Guinea.

When the British announced their Protectorate in 1896, they issued an arrest warrant for Bai Bureh, anticipating that he would incite opposition to the new “hut tax.”

The British, however, were unable to apprehend him, and thus started a long war of aggression, to which Bai Bureh bravely responded by organizing a large-scale guerilla insurrection that lasted 10 months.

He commanded troops from many Temne states, as well as Loko, Soso, and Limba combatants, and he held the upper hand over the far stronger British for the first four months.

Bai Bureh’s soldiers repeatedly surprised the British troops, launching heavy fire from behind hidden war walls before slipping away unnoticed into the bush.

Bai Bureh was known for his magical abilities, including the ability to become invisible and dwell under water for extended periods of time.

The British offered a £100 prize for information leading to Bai Bureh’s capture, but no one responded.

In 1898, he faced one of the world’s most well-trained and disciplined armies. He was able to fight for a peace agreement for over a year using little more than his craftiness, cunning, and bravado.

He is currently regarded as one of Sierra Leone’s greatest heroes.

Bureh’s popularity grew during the 1860s and 1870s as he effectively fought and won conflicts against other village chiefs and tribal leaders.

The inhabitants of the north believed they had discovered a warrior who would protect their land. Bai Bureh was crowned chief of Northern Sierra Leone in 1886.

The colonial government imposed a hut tax in Sierra Leone and throughout British possessions in Africa on January 1, 1893, seven years after he was crowned chief of Northern Sierra Leone.

Colonel Frederic Cardew, the governor of Sierra Leone, ruled that in order to fund the British administration, residents of the Protectorate would have to pay a tax based on the size of their huts.

The owner of a four-roomed hut would be charged 10 shillings per year, while those with smaller huts would be taxed five shillings.

Cardew imposed the tax the same year that two rebellions against British colonial control erupted in Sierra Leone’s hinterlands.

One was commanded by Temne chief Bai Bureh, 61, who led a mixed force of Tenme and Loko rebels in open revolt in the colony’s northeast.

The other insurrection was led by Mende chief Momoh Jah in the southeast. An arrest warrant issued by the colonial authority, meant to serve as a show of power to deter any possible rebellion, prompted Bureh to revolt.

Bureh launched the insurrection in February 1898, attacking colonial officials and Creole merchants with his rebels.

Despite the ongoing revolt, Bureh sent two peace overtures to the British in April and June of that year, assisted by Limba ruler Almamy Suluku’s intervention. Cardew turned down both offers because Bureh refused to submit fully.

Bureh quickly gained the support of several prominent African chiefs, including Kissi chief Kai Londo and Suluku, both of whom dispatched warriors and weaponry to Bureh’s rebels, who were fighting Captain W. S. Sharpe, a district commissioner who had previously been engaged in enforcing the tax with the Sierra Leone Frontier Police.

During the early stages of the insurrection, Bureh’s rebels were able to fight the British colonial forces to a standstill, with heavy deaths on both sides.

The revolutionaries also carried out attacks on anyone suspected of collaborating with the British, murdering many people, including Creole trader Johnny Taylor, who was cut to death by rebel soldiers.

Bai Bureh refused to acknowledge the colonial government’s hut tax. He did not feel the Sierra Leoneans had an obligation to pay taxes to outsiders, and he wanted all Britons to return to Britain and leave the Sierra Leoneans to solve their own problems.

A total of 24 chiefs submitted a petition to the colonial authority explaining why these restrictions were so difficult and harmed their cultures.

Furthermore, the chiefs saw the fee as an insult to their authority.

The colonial administration issued an arrest order for Bureh after he repeatedly refused to pay his taxes.

The British Governor of Sierra Leone, Frederic Cardew, also offered one hundred pounds as a reward for his capture; Bai Bureh responded by offering five hundred pounds for the governor’s capture.

Bureh declared war on Sierra Leone’s colonial authorities in 1898. The conflict was later dubbed the Hut Tax War of 1898.

Bai Bureh had earned the backing of several powerful native leaders, who provided troops and weaponry to help him fight Britain.

Bai Bureh’s troops not only participated in combat with the forces of the colonial government, but they also massacred scores of indigenous people whom they suspected of supporting the colonial government.

For several months of the battle, Bureh’s fighters had the upper hand over the colonial government’s better-equipped military forces, despite significant deaths on both sides.

By the 19th of February 1898, Bai Bureh’s men had entirely cut off communication between Freetown and Port Loko. They obstructed the road and the river leading to Freetown. Despite a warrant for their arrest, the colonial government’s forces were unable to defeat Bureh and his allies.

As the frustration grew, Sierra Leone’s colonial governor, ‘Governor Cardew,’ realized that he needed to do something drastic to win the war, so he ordered a “scorched earth policy,” a military strategy that aimed to destroy anything and everything that could be useful to the enemy; the British would end up burning entire villages, farmlands, and pastures.

This tactical shift had a tremendous impact on Bai Bureh’s military effort, as it lowered provisions to feed not only his warriors but also his subjects. He also recognized that the expense of repairs was mounting as the British pressed on with the new program.

Bai Bureh ultimately surrendered on November 11, 1898, to spare his people more tears and property losses.

The colonial authorities deported Bai Bureh, along with Sherbro chief Kpana Lewis and the strong Mende chief Nyagua, to the Gold Coast (now Ghana) as punishment for leading the insurrection, while 96 of his allies were convicted and killed.

Both Kpana Lewis and Nyagua died in exile, but Bai Bureh was allowed to return and was reinstated as Chief of Kasseh in 1905. Bai Bureh passed away in 1908, at the age of 68.

In central Freetown, Sierra Leone, there is a big statue of Bai Bureh. He is also depicted on various Sierra Leonean paper bills, and the Bai Bureh Warriors of Port Loko are a Sierra Leonean professional football club named after him.

Conclusion

The significance of Bai Bureh’s struggle against the British is not whether he won or lost the war, but that for a large number of months, a man with no conventional military experience was able to take on the British, who were immensely proud of their enormous military triumphs around the world.

Even though Bai Bureh’s uprising didn’t succeed in expelling the British from Sierra Leone, his story remains one of the more fascinating events that occurred.

Through the course of Bai Bureh’s rebellion, he garnered international attention for what was ultimately a pointless war.

And even though it ultimately failed, his struggle is still a symbol of defiance against colonialism.

Officers from the finest military institutions guided the British forces, where war is studied in the same way that a subject is studied at university.

The fact that Bai Bureh was not executed after his capture has led some historians to believe that this was due to reverence for his abilities as a foe of the Japanese.

He appears on various Sierra Leonean banknotes. The Bai Bureh Warriors, a Sierra Leonean professional football club based in Port Loko, is named after him.

Sources

https://talkafricana.com/bai-bureh-uprising-against-the-british-in-1898/

http://www.sierra-leone.org/Heroes/heroes5.html

https://adf-magazine.com/2018/10/bai-bureh-the-warrior-of-sierra-leone/